As individuals, we come from a variety of diverse identities and hold unique perspectives that helped us approach this report from a range of standpoints. Some of us identify with historically marginalized racial and ethnic groups; others do not. Our personal higher education journeys also vary. While one of us was a student during the COVID-19 pandemic, others were faculty working directly with students during this time. Each of us maintains an active research agenda concerned with the intersections of gender, race, ethnicity, higher education, and students’ experiences with basic needs insecurity. In entering this research, we understood that we brought both privilege and bias to the work. From our identities and lived experiences, we were able to use our positionalities to engage meaningfully with students in the focus groups, develop a culturally inclusive survey, shape our analytic approach, confront biases as they emerged, and critically examine the study’s findings and implications. As collaborators in this research, our positionalities specifically allowed us to offer insights into the findings and implications by drawing upon our own backgrounds, identities, and expertise areas.

Olaniyan, M., Magnelia, S., Coca, V., Abeyta, M., Vasquez, M., Harris III, F., & Gadwah-Meaden, C. (2023). Two pandemics: Racial disparities in basic needs insecurity among college students during the COVID-19 pandemic. The Hope Center at Temple University.

The way we use words is not mere symbolism but is necessary to achieving justice. Over the last year, the Hope Center’s Style Guide working group has aimed to deeply examine and consider the language The Center uses to better reflect the complexity of the humans we serve, through a narrative model that centers students as the experts they are of their own lived experiences.

As Radical Copy Editor Alex Kapitan writes, a style guide and the art of “radical copy editing” isn’t about absolutes; it’s about context and care…a style guide can never serve as a replacement for being in relationship with the real people you are writing about.” Nor is a style guide an attempt to police or shame others’ language choices. But it is an attempt to center the real people—the students—behind the statistics. The language we use and the framing of our research findings should empower instead of limit. It should define students by their assets and aspirations—not their deficits.

We must constantly examine and update our language as we continue to broaden and deepen our understanding of one another. In that spirit, our recommendations below are not set it stone. We will continue to revisit and revise them in light of the ever-evolving nature of identity-focused language.

The following considerations and recommendations have guided our choices for the language in this report. In a few instances, our recommendations slightly differed from the preferences of the authors of the report to whom we’ve ultimately deferred. We’ve noted those instances as they’re instructive and indicative of how subjective and fluid the quest for the most apt language can be.

Please note, for this report: when citing others’ work, we adopt the terms used in the original work. Therefore, when describing current findings, we use “Native American” for individuals who selected “American Indian or Alaska Native"” on our survey, “Indigenous” for individuals who selected “Indigenous,” “Latine” for individuals who selected “Hispanic or Latinx/Latina/Latino or Chicanx/Chicana/Chicano,” “Black” for students who selected “African American or Black.”

Stay tuned for the release of our full Style Guide on centering college students. We look forward to being in conversation and community with you all.

A note on Composite Narratives:

The authors of this report utilized a compositive narrative approach to convey the richness and complexity of students’ lived experiences while preserving anonymity of focus group participants. As the authors write, “These two considerations...led to the decision to present the data as a series of ‘composite narratives’. Using this approach, several individual interviews are combined to tell a single story. This approach, though rare, has been used when researching complex issues when anonymity is crucial, such as Piper and Sikes’s (2010) study of teacher–pupil relationships.”

A note on collectivizing language:

Specificity is a core objective we bring to our Style Guide work. Where and when possible, we encourage naming specific communities instead of using collectivizing language and recommend naming the specific identity/ies of the individual because the experiences of students facing basic needs vary greatly depending on their race, ethnicity, gender, sexuality, immigration status, class, and various other factors.

Deep dives:

Deep Dive on Capitalization of Black and White

We recommend capitalizing “White” for the following reasons:

- Capitalizing “White” advances racial equity by underscoring the significant and specific impact of Whiteness as a racial identity with social implications on policies, privilege and practice. Not capitalizing White while capitalizing other races may place Whiteness as the default, leading to the othering of non-white racial groups. Lack of capitalization frames whiteness as the neutral standard.

- The detachment of ‘White’ as a proper noun allows White people to sit out of conversations about race and removes accountability from White people’s and White institutions’ involvement in racism.

- We recognize that capitalization in the word White is often used by White supremacists to establish racial dominance over non-White races. We condemn the use of capitalization to threaten others and promote violence. Its capitalization is a way for us to recognize the history of racism in this country and acknowledge the power that Whiteness continues to hold in society.

We recommend capitalizing Black for the following reasons:

- Black as a proper noun calls attention to the shared history and identity of Black Americans that goes beyond just color. As Temple professor Lori Tharps writes in an op-ed for The New York Times, “Black with a capital B refers to people of the African diaspora. Lowercase black is simply a color.”

- Language has been used historically to stigmatize and dehumanize Black people and separate them from Whiteness. We align ourselves with predominantly Black publications and organizations like Ebony, Essence, the National Association of Black Journalists, etc. to inform the way we talk about Black communities in our work.

Deep Dive on Latine

Latinx recently emerged as a gender-neutral way to refer to individuals who trace their origins to Latin America in American English. However, research shows that only about a quarter of Americans who self-identify as Latin American use this word to describe themselves.

Since its rise in popularity, the word has been criticized for being out of touch with native Spanish linguistic principles.

Spanish is a gendered language, with nouns typically ending in “A” for feminine and “O” for masculine words. When referring to a group of mixed-gender and/or gender diverse people, the Spanish language defaults to using Latinos to refer to all genders. Academics advocating for the use of Latinx argue that masculine words should not be the default when talking about a mixed-gender group.

However, Spanish words typically don’t end with “x,” and the word “Latinx” is hard to pronounce for native Spanish speakers. It is also an unpopular word that is more widely used by English-speakers to identify Latine people instead of Spanish-speaking individuals using it to self-identify themselves.

For these reasons, we encourage using the word Latine as a gender-neutral ways of referring to groups of people originating from Latin America. We suggest Latine because it originated among Spanish speaking countries and is adopted by local activists in Latin America because the “e” sound at the end is both common and grammatically correct. Though it still isn’t very commonly used, we encourage its usage instead of “Latinx” because it originated in Hispanic circles, rather than seemingly being a White, western academic innovation.

Because we operate in policy spaces to achieve systemic change for students, it’s important to note that the U.S. Census Bureau has been on a long and problematic journey in categorizing and collectivizing those from Latine descent. Census records from 1930 show that in that year, the government counted Latine people under the catchall category “Mexican.”

It wasn’t until 1970 that the Census Bureau asked people in the U.S. if they were either “Mexican, Puerto Rican, Cuban, Central or South American, Other Spanish” or “No, none of these.”

In 1980, the U.S. government started using Hispanic on census forms as a collectivizing term with further options for Mexicans, Mexican-Americans, Chicanos, Puerto Ricans, Cubans, and “other,” (still not fully identifying the various countries whose residents constituted the Latin America diaspora).

Deep Dive on Talking About Mental Health

As we expand on our recommendations for using inclusive, non-judgmental and respectful language when discussing mental health, the Mental Health Coordinating Council’s recovery-oriented style guide grounds our suggestions:

“None of us should be defined by the mental health conditions or psychosocial difficulties that we experience, or by any single aspect of who we are. We should be respected as individuals first and foremost.”

We recommend using people-first language instead of identity-first language. That is, instead of saying:

- mentally ill student,

- depressed student

- anxious student, etc.,

we recommend using students experiencing mental health conditions, or students experiencing symptoms of anxiety or depression to ensure that the subject’s entire personhood isn’t defined by their mental health condition.

Often, when talking about mental health, a common language pitfall is the use of deficit-framed language that limits the subjects and sensationalizes their experiences with mental health. Here are some examples of deficit-framed phrasing:

- Student X suffers with mental health conditions

- Student Y is afflicted with anxiety

- Student Z is a victim of depression

Instead, we recommend using asset-framed language that does not victimize the subjects being talked about, and advances that they are whole, complete and empowered individuals outside of their mental health diagnosis. Here are examples of asset-framed phrases:

- Students X experiences symptoms of anxiety

- X percent of students were diagnosed with a mental health condition

- Student Y has lived experience with trauma

Executive Summary

Higher education is essential for creating a more equitable, prosperous, civic-minded, and healthy society. Yet, there remain disparities in access and success in higher education based on race and ethnicity. Racist policies and structural barriers mean that not all students have equal opportunities to attain an education and succeed in college. These disparities were further magnified during the COVID-19 pandemic. Indigenous and Latine Americans were more likely to get sick with COVID-19, and Black, Latine, and Asian women were more likely to lose work.[1] Meanwhile, college enrollment has decreased precipitously among Black and Native American men.[2] [Refer to our Style Guide note above in regard to our categorization of students.]

This report explores how students’ college experiences during the pandemic varied by race and ethnicity. From the findings, we learn lessons crucial to the nation’s continued recovery. We look specifically at students’ basic needs security, including their mental health, access to technology, and use of campus and public supports. The data come from the fall 2020 #RealCollege Survey, completed by more than 195,000 students attending 202 colleges and universities in 42 states. We also draw on data from 23 focus groups, four of which were conducted at the start of the pandemic in spring 2020 (the rest were conducted in 2019). These groups included 140 students attending three community colleges in two states.

The fall 2020 #RealCollege survey data reveal wide variation in college experiences based on race and ethnicity:

- At over 70%, rates of basic needs insecurity were highest among Indigenous, Native American, and Black students. Meanwhile, the rate of basic needs insecurity among White students was 54%.

- Pacific Islander and Indigenous students had the highest proportion who experienced challenges in accessing the Internet or a computer, with four in five students facing that challenge at four-year colleges and universities.

- Approximately 7 in 10 Indigenous, Native American, Pacific Islander, and Black students who were employed also experienced basic needs insecurity.

- Approximately 8 in 10 Indigenous and Native American students experienced basic needs insecurity despite receiving a Pell Grant.

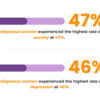

- Indigenous women experienced the highest rates of anxiety and depression, at rates of 47% and 46%, respectively.

- Among students experiencing basic needs insecurity, Southeast Asian, White, and Asian American students were the least likely to use supports, while Indigenous, Native American, and Black students were the most likely to use supports.

In focus groups, students also expressed that college staff showed little care and compassion, despite the added stress of attending college during the pandemic.

Quotes from students are included throughout the report. In some instances, students’ shared experiences may be upsetting. We include these not to cause harm, but rather to illuminate the reality of being in college today. Some quotes also suggest that the students were experiencing challenges with their mental health. Students experiencing more than minimal symptoms of depression were referred to the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline.

These are distressing disparities that are likely to contribute to students’ ability to earn a college credential. They also illuminate the work colleges, governments, and community leaders must now undertake to ensure an equitable recovery.

The work could begin by making emergency aid a permanent feature of financial aid, increasing funding to institutions that serve high numbers of historically marginalized students, and ensuring that students can easily access public benefits and campus supports.

These steps, along with further recommendations for federal and state policymakers, and institutions, provided at the end of this report, are vital to solving unacceptable racial and ethnic disparities in student outcomes. They are also pivotal to ensuring the nation’s long-term health and prosperity.

These steps, along with further recommendations for federal and state policymakers, and institutions, provided at the end of this report, are vital to solving unacceptable racial and ethnic disparities in student outcomes. They are also pivotal to ensuring the nation’s long-term health and prosperity.

Introduction

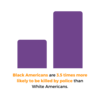

Structural inequities by race and ethnicity are not only deeply woven into the U.S. system of higher education, but fundamental to its initial design. Higher ed was not built for student success, much less the success of non-White students.[3] From the rising cost of college to racially biased admissions practices, students from minoritized racial and ethnic groups face numerous barriers simply accessing higher education.[4] Those students who successfully enroll face yet another set of challenges once on campus; they are more likely to experience hunger and homelessness, take on student loan debt, struggle to balance family obligations, and face higher unmet financial need.[5] These challenges accumulate and have long-term financial consequences on students’ financial security. Since the 1980s, the racial wealth gap has continued to widen, with White families maintaining eight times more wealth than Black families and five times that of Latine families.[6] Systemic factors, such as disparities in student debt, drive racial inequalities in owning and building wealth.

For many decades, there has been a disproportionate lack of public investment in colleges that primarily serve students of color.[7] Longstanding and intentional underfunding of Historically Black Colleges and Universities (HBCUs) created significant financial challenges for these storied institutions.[8] Students from minoritized racial and ethnic groups are also over-represented at the nation’s community and technical colleges (institutions that are also vastly underfunded), which enroll 45% of America’s undergraduate students, but 56% of its Latine students, 54% of Pacific Islander students, and 51% of Black students.[9]

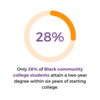

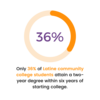

Inequitable distribution of funding and enrollment has driven sharp disparities in student outcomes. Today, Latine and Black students are more likely to leave college without a degree.[10] Only 28% of Black community college students and 36% of Latine community college students attain a two-year degree within six years of starting college.[11] Indeed, disparities in rates of college completion remain stagnant even as college enrollment rates have increased.[12]

The COVID-19 pandemic further compounded these disparities. In fall 2021, there was a disproportionate decline in college enrollment among Black and Native American men at two-year public colleges.[13] There were also disparities in employment by race and gender. Black, Latine, and Asian women accounted for the highest rates of job losses.[14] Black, Indigenous, and Latine students were more likely to know someone who died of COVID-19.[15] Moreover, Black and Latine parenting students struggled to juggle coursework with caring for their children.[16] Students at HBCUs faced higher rates of basic needs insecurity.[17]

After the pandemic began, Asian Americans[20] and Pacific Islanders faced a sharp rise in hate crimes and violence, with rates of racially motivated violence increasing by 145% in 2020 compared to 2019.[21] The spike in anti-Asian hate crimes began in March and April of 2020, corresponding with a rise in xenophobia and racism related to conspiracy theories about the source of the pandemic.[22] Across the country, students organized to combat anti-Asian hate and bias on college campuses.[23]

Because of the increase in racist violence, many Black, Asian American, and Pacific Islander students felt as though they were living amid a “double pandemic” or “two pandemics” from both the coronavirus and racial trauma.

As the nation recovers from the pandemic, higher education is unfortunately poorly poised to rebound from these challenges, particularly when many underresourced colleges are experiencing financial shortfalls due to declines in enrollment.[24] Colleges and policymakers must prioritize solutions to solving longstanding disparities in student outcomes.

Higher education is an essential part of the nation’s collective and individual economic prosperity, but the legacy of systemic and structural racism has prevented systemically marginalized students from a fair shot at obtaining a college degree or credential, graduating without or managing their student debt, and finding a good job. Unequal access to postsecondary credentials contributes to growing economic inequality and stands at odds with the American ideals of equality and opportunity.[25] In this report, we outline the challenges and barriers to academic success that students from minoritized groups encountered during the pandemic. To address these issues, we recommend policymakers and college leaders improve access and success in higher education for minoritized students.

The Data

The data in this report come from two sources: focus groups conducted with community college students from 2018 to 2020 and the fall 2020 #RealCollege Survey. Quotes from students were in response to an open-ended question asking what the world needs to know about what college was like during the pandemic.

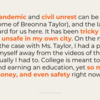

From 2018-2020, a total of 23 focus groups were facilitated by team members of the Community College Equity Assessment Lab (CCEAL), a national research laboratory at San Diego State University.[26] Four of these case studies took place in the first couple months of the pandemic, February and March 2020. The focus group sessions lasted about 60-90 minutes and took place at one of three community colleges; two of which are in Northern California, while the other is in South Carolina.

A total of 140 students participated in the focus groups. Students self-identified their gender, race, ethnicity, enrollment status, and employment status. Students included 66 women, 68 men, and 6 gender non-conforming individuals. Fifty-six students in the focus groups were Black or African American, 34 were Mexican or Mexican American, 19 were White, 17 were Multiracial, and four were Filipino. Ten students did not provide information on their race or ethnicity. Two-thirds of students in the focus group were enrolled full-time and nearly 58% of students were employed. For additional details on the focus groups, including information about recruitment and data analysis, see the web appendices.

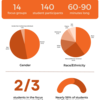

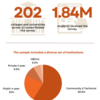

In 2020, from August to November, 202 colleges and universities in 42 states fielded the #RealCollege Survey. In total, 1.84 million college students received the survey and about 195,000 responded, yielding an 11% response rate. The sample included a diverse set of institutions: 130 community and technical colleges, 51 public four-year colleges and universities, and 21 private four-year colleges and universities. Among these, 14 were HBCUs and five were Tribal Colleges and Universities (TCUs).

Racial and Ethnic Categories

In the survey, we included ten categories for students to indicate their racial and ethnic identity presented in random order except that “Other” always appeared last. The categories are not mutually exclusive—students could select multiple categories. In total, students from minoritized racial and ethnic groups comprise 58% of the sample. The following groups were used in our racial and ethnic classifications:

- White or Caucasian

- African American or Black

- Middle Eastern or North African or Arab or Arab American

- Southeast Asian

- American Indian or Alaska Native

- Indigenous

- Hispanic or Latinx/Latina/Latino or Chicanx/Chicana/Chicano

- Pacific Islander or Native Hawaiian

- Other Asian or Asian American

- Other

For brevity and to reflect evolving language conventions and the recommendations of our style guide [refer to our Style Guide note at the top of the report], we use the following terms to describe these groups in the current report: White, Black, Middle Eastern, Southeast Asian, Native American, Indigenous, Latine, Pacific Islander or Native Hawaiian, Asian American, and Another Race, respectively.

These categories allow us to compare students’ experiences by race and ethnicity. However, because this list does not fully capture the range of racial and ethnic identities, there were limitations to interpreting results within each group. For instance, race and ethnicity were combined within some categories even though ethnic differences between groups may influence outcomes. In addition, nationality was not taken into consideration, which further limits our understanding of how culture influences students’ experiences. As a second limitation, we used consolidated racial and ethnic categories for analyses in which the sample sizes were small within groups, or when similar outcomes were present between groups. As an example, students who identified as Southeast Asian, other Asian, or Asian American were grouped together. However, the experiences among Asian and Asian American students may vary based on country of origin, cultural differences, immigration status, and unique history.

What are Students’ Basic Needs?

The Hope Center defines students’ basic needs as access to the following: nutritious and sufficient food; safe, secure, and adequate housing—to sleep, study, cook, and shower; healthcare to promote sustained mental and physical well-being; affordable technology and transportation; resources for personal hygiene care; and child care and related needs.[27] Basic needs security is the ability to consistently meet the minimum requirements that one’s body and society require of them to function.

This definition makes the inclusion of needs like technology and food in the same category of “basic” clear—one now needs access to technology to function in society in the same way one needs food for their body to function. It is crucial to understand that basic needs insecurity, the inability to do as mentioned, is more often than not a systemic failure rather than one that has anything to do with the determination, ability, or willingness of an individual. Student basic needs insecurity occurs when there is a mismatch between structural support for students’ basic needs, and a student’s needs. This mismatch can occur in several ways: from an inadequate ecosystem of support, systemic barriers to access those supports, insufficient outreach around those supports, etc.

The 2020 #RealCollege Survey measured three primary types of basic needs insecurity:

- Food insecurity is the limited or uncertain availability of nutritionally adequate and safe food, or the ability to acquire such food in a socially acceptable manner.[28] The most extreme form is often accompanied by physiological sensations of hunger. The 2020 #RealCollege Survey assessed food security using the U.S. Department of Agriculture’s (USDA) 18-item set of questions.[29]

- Housing insecurity encompasses a broad set of challenges that prevent someone from having a safe, affordable, and consistent place to live.[30] The 2020 #RealCollege Survey measured housing insecurity using a nine-item set of questions developed by our team at The Hope Center. It looks at factors such as the ability to pay rent and the need to move frequently.

- Homelessness means that a person does not have a fixed, regular, and adequate place to live. In alignment with the McKinney-Vento Homeless Assistance Act, students are considered homeless if they identified as experiencing homelessness or signs of homelessness (for instance, living in a shelter, temporarily with a relative, or in a space not meant for human habitation).[31] We use this inclusive definition of homelessness because students who are experiencing homelessness or show signs of homelessness face comparable challenges.[32]

In this report, we present rates for students experiencing “any basic needs insecurity,” meaning a student was experiencing at least one of the following: food insecurity, housing insecurity, or homelessness. While our measures of basic needs insecurity assess students’ needs during distinct periods—the prior month for food insecurity and the prior year for housing insecurity and homelessness—basic needs insecurity is fluid, and students’ experiences with basic needs may change over time.

For additional information on our methods, refer to the web appendices. Complete findings from the survey are available in The Hope Center’s report #RealCollege 2021: Basic Needs Insecurity During the Ongoing Pandemic.

Life During the Pandemic: Four Racially Minoritized Students' Experiences

Here, we present four student composite narratives to highlight the various challenges that students faced during the pandemic. These composite narratives draw on our 23 focus groups at three community colleges and use information from multiple students to tell one story.[33] To further preserve the anonymity of focus group participants, the names of students and colleges used in these composite narratives are pseudonyms. Each composite narrative reflects common themes heard across focus group sessions but features various student perspectives (e.g., students formerly incarcerated, as well as students impacted by the carceral system).

Even the most determined students struggle through college, and their struggle is often due to an accumulation of events. Eddie, a Pacific Islander student from Washington, enrolled in his first semester at Central California Community College (Central) in fall 2019 at the age of 23. While in high school, Eddie was a promising student-athlete, having received numerous awards and scholarship offers to play college basketball upon graduation. However, during his senior year, he suffered an injury that not only ended his season, but also any opportunities for athletic scholarships. Although he enrolled at a local university, his attempt to make the team as a walk-on was unsuccessful. Eddie became less motivated at school and reduced his academic course load. He also began working full-time, which impacted his energy for school, and he eventually dropped out. However, Eddie never let go of his dream of playing college basketball. One day at the grocery store where he worked, Eddie happened to meet an assistant coach from a California community college who was in town for a basketball camp. After several subsequent conversations, Eddie decided to move to California in the hope of transferring to a university. In fact, the community college had a rich history of helping players secure athletic scholarships from four-year institutions.

Upon arriving, Eddie was shocked to learn that California’s community colleges do not offer athletic scholarships. He also learned that because he was not a California state resident, his cost of attendance would be nearly three times the cost of an in-state student. Moreover, he had no transportation, no place to live, and could not afford housing. Eddie was under the impression that he would receive a grant to cover his academic expenses, housing support, and a stipend for food and other living expenses as this is standard practice at most community college athletic programs. Despite these challenges, the opportunity to play basketball instilled motivation and Eddie decided to stay. Thankfully, a teammate invited Eddie to live in a converted garage at his parents’ home until he could find a place to live. Also, the college had a partnership with the local department of transportation that allowed community college students to ride the city bus for free. This made it possible to get to and from school for classes and basketball each day. Unfortunately, Eddie had very little food to eat. Every now and then, he pulled together a few dollars to purchase a bean and cheese burrito from Taco Bell. He also became skilled at finding campus events that served food. But he never had a full home-cooked meal and had virtually no access to healthy, nutritious food.

During the fall of 2019, Eddie struggled physically, financially, academically, and emotionally, but somehow made it through. He completed 4 classes and earned a 2.3 grade point average (he began with 5 classes but withdrew from his statistics class because he was not doing well). Eddie was looking forward to the spring semester, but because of the pandemic the basketball season was canceled. This was devastating for Eddie; with the abrupt ending of the season, he felt a loss of community with his teammates and struggled with distance learning. Being separated from his family in Washington state, he found himself alone in a new city and unsure of his future athletic career.

During the pandemic, parenting students often struggled with juggling multiple responsibilities. Sasha, a Black college student, was enrolled full-time as a STEM (Science, Technology, Engineering, and Math) major at a four-year institution. In addition to her coursework, she worked part-time at a mechanical engineering lab on campus. Sasha has two children, including a three-year-old who was enrolled at the university’s child development center and a seven-year-old who was in second grade at a nearby elementary school. Her spouse worked as a full-time health care provider, and together, they arranged their schedules to accommodate each other’s responsibilities, as well as morning drop-offs and afternoon pick-ups of their children.

In January 2020, her partner’s work hours began increasing due to the onset of the pandemic. With this change, Sasha took on the additional duties of dropping off her children in the morning. However, this created a conflict for her morning chemistry class. Her professor frowned upon anyone being late to class and informed students that their grade would be reduced by 5% after three tardies. This caused Sasha much anxiety and stress given the staggered drop-off times of her two children.

Meanwhile, Sasha’s family was taking extra protective measures as her partner became increasingly concerned with his potential exposure to COVID-19. When he arrived home, he immediately changed from his medical scrubs and washed them. Sasha had to keep the children occupied when her partner arrived home because they did not understand the potential risk.

In March 2020, as the pandemic worsened, all of Sasha’s classes became virtual, and her children’s schools closed. Suddenly, they were all quarantining at home together. This created a stressful home environment, as Sasha tried to remain focused on her own virtual learning, while ensuring that her seven-year-old was also logged in remotely for second grade. She constantly had to keep her four-year old occupied because the child development center on campus was closed due to the pandemic. Sasha was continuously shifting from parent to student throughout the day. As the pandemic fatigue set in, she did not feel that she could share her struggles as a parenting student with her professors as they had not been empathic in allowing her to turn in late or missed assignments.

Many students lost their jobs due to the pandemic, causing them to adapt to challenging living and learning environments. Majoring in business administration, Vince, a 26-year-old Hmong community college student, lived in a three-bedroom apartment with his friends and worked full-time. With the closure of local businesses, Vince became unemployed and began struggling to pay for his portion of the rent. He decided to temporarily move into his family’s multigenerational, two-bedroom apartment. His household included his parents, his elderly grandfather, his sister, and her two children. Each night, the family cleared the living room floor and set up an air mattress for Vince. In the mornings, he was woken up by family members who have shifted to working from home due to the pandemic. Vince helped around the house when he could, becoming the primary caretaker for his elderly grandfather and his younger nieces. As the only family member enrolled in college, he also contributed by collecting free meals and household essentials from the emergency drive-thru distributions hosted by his community college.

While Vince was only enrolled in two classes, he found it incredibly difficult to join his synchronous classes due to the poor Wi-Fi connection at home. He strengthened his bandwidth by keeping his camera off but was still distracted by his family members who complained that they, too, needed the internet bandwidth. To avoid conflict at home, Vince often ended up disconnecting from class before it was officially over. He also stayed up late when the house was quieter so that he could complete his homework. A few weeks into remote learning, Vince was able to obtain an internet hotspot device from school, which kept him from disrupting the household connection. However, he found himself uncomfortable turning on his camera due to his busy household. Unlike some students who had their own room or workspace, Vince was worried that his peers and instructors would pass judgment on his living conditions, particularly as an Asian American immigrant household.

In a matter of a few short weeks, Vince’s life had drastically changed. He went from working full-time as an independent college student to moving back home, becoming a caretaker, and adjusting to distance learning.

The rapid shift to online learning at the beginning of the pandemic raised the stakes of longstanding inequities in access to technology and employment. Students previously incarcerated were particularly vulnerable to these challenges. Carolina was a 33-year-old Puerto Rican woman who was a full-time community college student. Carolina, a carceral system-impacted student, found adjusting to college difficult; she had limited experience with technology and was unsure how to navigate college systems. Luckily, Carolina was a participant in a college program that supports formerly incarcerated and carceral system-impacted students, which gave Carolina access to individual counseling, academic enrichment workshops, and peer mentoring. Carolina also relied on her peers to assist with the computer applications, as well as the computer lab and internet access at her campus.

As a valued member of the program, Carolina received a verbal employment offer to join the office staff. She was excited about the opportunity to be part of a program that has helped her. While her prior felony conviction history had been a barrier in obtaining employment, Carolina was hopeful that her carceral record could be expunged with the support of the expunction clinic offered by her campus. However, there was concern and ongoing discussions regarding Carolina’s history within human resources. The college’s governing board has asked her to write a statement about her rehabilitation and readiness for employment. Carolina felt confused, hurt, and embarrassed that she was being asked to prepare a statement to prove that she was worthy of working at the campus.

Meanwhile, as COVID-19 cases began rising, Carolina’s college announced a shift from face-to-face instruction to remote learning. With the sudden temporary shift, Carolina continued to attend class using her smartphone. It took several weeks for her institution to make laptops and internet hotspot devices available to students. Once she could receive these items, she continued with her coursework and reconnected with her peers from the program. However, she noticed not all her peers were joining virtually. Furthermore, the physical distance from her peers made it difficult for Carolina to seek help with computer applications. As the campus transitioned to remote operations, Carolina’s employment offer stalled and she relied on stimulus checks to get by. She looked forward to the time when she could rejoin her peers and campus community.

Barriers to Graduation: Endemic Problems during the Pandemic

The composite narratives depict students’ experiences throughout the pandemic. Below, we examine four of the most common challenges that students shared with us. Specifically, we discuss the pandemic’s impact on students’ access to technology, basic needs insecurity, and mental health, as well as the supports that colleges provided for their students.

Disparities in Access to Technology During the Pandemic

The rapid shift to remote learning in spring 2020 exacerbated racial and ethnic disparities in access to technology that existed prior to the pandemic. Carolina’s difficulty with technology illustrates some of the technological challenges that students faced. When campuses closed, students lost access to on-campus resources previously used to complete assignments. In addition, the pandemic presented challenges for students with limited broadband access. A strong and reliable internet connection became a necessity for virtual learning. However, parts of the country have limited access to broadband, particularly in areas with larger minoritized populations such as in rural tribal areas and many Black and Latine neighborhoods.[34] Vince’s experience likely mirrors that of many students. Poor Wi-Fi prevents students from participating in synchronous classes.

Nationally, racial and ethnic disparities exist in access to technology (Figure 1). The proportion of Pacific Islander or Native Hawaiian as well as Indigenous students experiencing challenges to accessing internet or a computer at both two- and four-year colleges was the highest, with about four in five students experiencing problems with technology at four-year colleges and three in four experiencing difficulties at two-year colleges. The percentage of Pacific Islander or Native Hawaiian students who experienced technological challenges with their laptop or computer was 10 percentage points higher than their Asian American peers. Middle Eastern, Black, and Asian American students experienced fewer problems with their internet or computer.

In addition to racial and ethnic differences, access to technology differed by college sector. Overall, a higher percentage of students at four-year colleges experienced problems accessing technology than students at two-year public colleges. This was consistent across all racial and ethnic groups, as shown in Figure 1.

For more information on how each measure of basic needs insecurity was created in the following figures, along with details on the racial and ethnic categories included in these figures, refer to the web appendices.

Disparities in Basic Needs Insecurities During the Pandemic

Numerous students experienced challenges with basic needs insecurity throughout the pandemic. Many students were displaced from housing or were cut off from access to balanced meals. Challenges disproportionately affected students from minoritized racial and ethnic groups.[35] Eddie, upon entering college, received no financial support for food or living expenses. Because Eddie only had a small amount of savings, he—like many other students—could not afford housing on his own.

The evidence of basic needs insecurity is overwhelming: students identifying as Indigenous, Native American, and Black experienced the highest rates of basic needs insecurity, with rates above 70% (Figure 2). Moreover, these students experienced the highest rates of housing and food insecurity when compared to their peers. Indigenous and Native American students were also disproportionally impacted by homelessness, with about one in four students experiencing homelessness.

Disparities in Basic Needs Insecurity by Employment and Use of Federal Aid

While many students rely on income from their jobs and federal aid to attend college, these financial supports are often insufficient to cover their basic needs—let alone tuition and fees. Moreover, students’ wages and hours were more unstable at the start of the pandemic. For example, Vince’s experiences during the pandemic demonstrate common challenges. Due to a rise in unemployment during the pandemic, he struggled to contribute resources for his household. To cope, Vince relied on access to emergency food distribution centers to meet the needs of his family.

Notably, financial instability throughout the pandemic disproportionately impacted students from minoritized racial and ethnic groups. While some students worked or received Pell Grants to cover the costs of college, these financial resources were often not enough to support students’ basic needs. While rates of basic needs insecurity were prevalent across students, higher percentages of Indigenous, Native American, Pacific Islander or Native Hawaiian, and Black student workers and Pell Grant recipients experienced basic needs insecurity (Figure 3).

Disparities in Mental Health

At the onset of the pandemic, many colleges and universities closed their campuses and limited in-person services, which led to students losing access to on-campus mental health care.[36] During this time, many students also found themselves isolated from their social support networks. This combination of stressors and the uncertainty of returning to campus and health concerns regarding COVID-19 contributed to students’ symptoms of anxiety and depression.[37] Many students also faced mental health challenges from a rise in race-related hate crimes and racial violence.[38]

Students’ experiences of anxiety and depression symptoms differed by race and gender (Figure 4.1 and 4.2). Overall, symptoms of anxiety and depression were more common among female students compared to male students. Across racial groups, anxiety and depression disproportionately impacted female Indigenous, Pacific Islander or Native Hawaiian, and Native American students—42-47% experienced anxiety; 40-46% experienced depression. In addition, gender differences in anxiety and depression were notable among Black students. About one in four Black men experienced depression, while about one in five experienced anxiety. However, more than 32% of Black women experienced anxiety and 34% experienced depression.

Black men experienced lower rates of depression and anxiety symptoms in our study. However, as suicide rates among Black men and boys rise nationally[39], it is important to note that the mental health screens utilized may fail to capture the mental health symptoms and experiences of Black men[40]. Further, research indicates that despite lower symptom rates, Black men experience more severe and chronic mental health symptoms and reduced access to mental health care compared to White men[41].

The Need for a Culture of Care

During the pandemic, there was a need for empathy from college faculty, staff, and administrators. Many students perceived indifference and lack of compassion from faculty regarding students’ personal challenges. Despite the many challenges students faced, faculty held students to the same, if not higher, standards of academic performance.[42] Sasha, like several students, experienced conflicts with their professors due to conflicting priorities caused by the pandemic. Some faculty were unyielding on course requirements despite the many challenges hindering academic coursework among students like Sasha.

While many students felt unsupported by their instructors during the initial months of the pandemic, several colleges and universities strived to provide student resources, including expanding available campus support for those in need. For example, some colleges partnered with local service organizations to ensure equitable access to supports.[43] In addition, The Hope Center found that 180 colleges and universities utilized emergency aid programs in fall 2020 to help connect students to supports.[44]

Despite efforts by colleges and universities, we found that few students who experienced basic needs insecurity used campus supports during this period. Additionally, use of supports differed by race and ethnicity (Figure 5). For example, Indigenous, Native American, and Black students experienced the highest rates of basic needs security—75%, 70%, and 70%, respectively—but also utilized campus supports at higher rates.

Among those facing basic needs insecurity, the two most common reasons students did not use campus supports were because they did not think they were eligible, or they thought others needed these programs more than themselves (Figure 6). Across racial and ethnic groups, a lower percentage of non-White students knew that supports existed or were available to them. Similarly, a higher percentage of White students than students from other racial and ethnic groups knew how to apply for these supports, whereas lower percentages of Southeast Asian, Asian American, and Indigenous students knew how to apply for supports.

In contrast to the use of campus supports, many students who experienced basic needs insecurity did receive public benefits, such as food and housing assistance (Figure 7).[45] Use of public benefits was highest among Indigenous students, with nearly two-thirds receiving those benefits. While students from minoritized racial and ethnic groups experienced more difficulty securing their basic needs, they did utilize supports more than those with lower rates of basic needs insecurity.

Conclusion and Recommendations

The pandemic drove a sharp decline in enrollment and completion rates, with students from minoritized racial and ethnic groups disproportionately affected. Many of these students faced obstacles that impeded their academic success. Basic needs insecurity, poor mental health, difficulty accessing technology, and limited access to supports presented disparate challenges based on students’ race and ethnicity. While these challenges existed prior to the pandemic, the pandemic exacerbated these issues and furthered the racial and ethnic disparities in higher education.

At many institutions, especially community colleges, enrollment has never returned to pre-pandemic levels.[46] New survey data suggest that struggles with basic needs and concerns about college costs drove many students to stop out and continue to keep many students from considering higher education.[47] As the nation exits the pandemic era, students need systemic changes in higher education policy and practice to reduce structural barriers to their success.

Recommendations for Federal Policymakers

During the pandemic, Congress made the first-ever federal investment in emergency aid—providing a total of nearly $40 billion to help students survive and stay enrolled in college. Unlike traditional federal financial aid, emergency aid grants help students deal with unexpected expenses that can otherwise throw them off track from a degree or credential. Given that Black, Latine, and Indigenous students experience basic needs insecurity at higher rates, this type of financial aid is highly beneficial to improve equity in student success. Federal funds for emergency aid during the pandemic have now been exhausted, but students still urgently need this resource. Congress should make federal funding for emergency aid permanent by allowing the Supplemental Educational Opportunity Grant (SEOG) program to operate permanently as emergency aid.[48] Additionally, legislation such as the Emergency Grant Aid for College Students Act offers another pathway for sustaining emergency aid programs on a long-term basis.[49]

Congress should substantially increase funding for the Basic Needs for Postsecondary Students Program (“Basic Needs Grants”) administered by the U.S. Department of Education (ED).[49] This competitive grant program provides funding for HBCUs, Tribal Colleges and Universities (TCUs), Minority-Serving Institutions (MSIs), and community colleges to build programs that comprehensively address basic needs insecurity, such as connecting students with public and tax benefits, building data-sharing agreements, and screening and surveying students about their basic needs.

Students and their families should be made aware of their eligibility for public benefits proactively and have a seamless process for enrolling. Colleges can use financial aid data from the Free Application for Federal Student Aid (FAFSA) to connect students with public benefits like the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP), broadband discounts, health insurance coverage, and more.[50] The Administration should establish data-sharing agreements between ED and all federal agencies that administer public benefits programs to automatically and regularly identify students eligible for support.

MSIs, HBCUs, regional public comprehensive universities, and open-enrollment public institutions are more likely to enroll minoritized students yet receive far less public support. Additionally, despite generally lower tuition at these colleges, students still face significant out-of-pocket expenses. Congress should create a new partnership that leverages and guarantees additional state support for higher education and provides at least two years of tuition-free education beyond high school for students at public institutions and MSIs. Congress can look to the America’s College Promise Act, Debt-Free College Act, and College for All Act as models for this partnership.[50] In establishing the partnership, Congress should fund institutions based on total student headcount and avoid inequitable full-time equivalent (FTE) enrollment formulas.[51]

Through the American Rescue Plan Act, Congress passed an expansion of the Child Tax Credit (CTC) and delivered the credit monthly to families with children throughout the second half of 2021. This expansion expired at the end of December 2021, despite its massive success in reducing child poverty and helping families, especially Black and Latine families, meet basic needs.[54] Congress should pass a long-term expansion of the monthly CTC and ensure that parenting students have the necessary information to apply for and receive the benefit. And, ED should add the CTC to the list of benefits included on the FAFSA and conduct outreach to students and families that may be eligible for the credit.

Current rules in public benefit programs like SNAP, TANF, and the Child Care Development Block Grant contain harmful restrictions that greatly reduce access for systemically marginalized students. The federal government should recognize that enrollment in higher education is equivalent to work and that restrictions on public benefits are built on racialized foundations and outdated assumptions around college students’ experiences. Policymakers should broadly consider postsecondary education a qualified activity for meeting any compliance, work participation, or core activity requirements for public benefits and reduce the need for students to work long hours while enrolled in school.

Students face substantial barriers to qualifying for SNAP through a series of complex eligibility rules. Most students with low incomes only qualify for SNAP by working 20 hours per week on top of their coursework—a rule that both Congressional leaders and Administration have acknowledged is outdated.[55] The SNAP student rules create significant administrative burdens, confuse students, and worsen food insecurity. Through the Coronavirus Response and Relief Supplemental Appropriations Act (CRRSAA), Congress temporarily expanded SNAP eligibility to college students who have a $0 EFC (Expected Family Contribution) or are eligible for federal or state work study, thereby expanding the potential number of students who could receive SNAP and reducing food insecurity among the students most likely to experience it. However, these flexibilities ended when the public health emergency expired. Congress should revive these SNAP eligibility improvements and go further to remove all SNAP restrictions that specifically target and restrict college students.[56] Enrollment in higher education should satisfy all activity and participation requirements. The EATS Act[57] and Student Food Security Act[58] are legislative models.

Students are stripped of federal financial aid, and often state aid, if their academic performance falls below the “Satisfactory Academic Progress” (SAP) standards: GPA below 2.0 or a course completion rate below 67%. However, a study of California community college students found that not only do one in four students fall afoul of the arbitrary SAP standard, but SAP failure rates are highly inequitable: Black and Native American students are twice as likely to fail SAP as White students.[59] Many students may fail SAP standards because they are struggling with basic needs insecurity. Congress should reform SAP to allow more options for warnings or appeals and to reduce harsh penalties or remove SAP from federal financial aid entirely. The U.S. Department of Education should revise SAP regulations and guidance to ensure that students who leave after SAP violations will have their financial aid eligibility restored after no more than two years and establish more flexibility for students to appeal a loss of eligibility due to extenuating circumstances, including basic needs insecurity.

Black students face a long history of housing discrimination, redlining, and structural racism in the housing and rental markets. Given high rates of housing insecurity and homelessness among Black and other minoritized students, the federal government should work to include students in initiatives and programs meant to help families afford stable housing. For instance, it can eliminate restrictions that prevent college students from qualifying for the Low-Income Housing Tax Credit (LIHTC) program; increase funding and eligibility for Homeless Assistance Grants; revive and expand the Emergency Rental Assistance Program (ERAP) and ensure that students are eligible;[60] and remove student restrictions in public housing programs. The U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) should work to identify programs and partnerships within and across colleges and universities that can be replicated and have a specific focus on equity.

Recommendations for State Policymakers

Across the country, radical state legislators have been promoting legislation that would abolish campus diversity, equity, and inclusion (DEI) offices, ban diversity trainings, prohibit diversity statements for admissions or hiring, wipe out any remaining affirmative action policies, and restrict faculty and staff from discussing institutional racism or considering theories that seek to understand racial inequity.[61] Anti-DEI legislation sharply restricts or prohibits colleges from addressing racial inequities on their campus, chills free speech, and sends a message to structurally marginalized students that they are not welcome. Defeating this type of legislation is essential for higher education to be able to close racial and ethnic disparities in student outcomes. student outcomes.[62]

College students, particularly minoritized and first-generation students, often do not enroll in public benefit programs that would improve their chances of persisting and earning a degree due to poor outreach and complex eligibility rules. To reduce barriers to support for students experiencing basic needs insecurity, some colleges have hired “benefit navigators” to connect students to public benefits and campus or community resources that support non-tuition expenses.[63] States should require colleges operating in their states to establish benefit hubs or navigators on campus and fund them to do so, as modeled under state law in Oregon, California, Illinois, and Washington.[64]

State higher education, K-12, workforce, and human service agencies should collaborate to conduct targeted outreach and education about public benefits, determine eligibility for benefits and programs, and identify eligibility rules and barriers that could be waived or streamlined. For example, states should proactively inform students and their families about public benefits like SNAP and provide clear guidance and support for colleges engaged in similar efforts.[65]California requires public colleges to use data from the Free Application for Federal Student Aid (FAFSA) to identify income-eligible students for SNAP, notify them of their potential eligibility, and provide contact information for college staff who can assist them with their application. Virginia requires public colleges to advertise the process for applying for SNAP prominently on their websites, in orientation materials, and in campus-wide emails. At the federal level, ED encourages state higher education agencies to collaborate with state SNAP agencies also conduct direct and targeted outreach on SNAP.[66]

States administer many federal public benefit programs, giving them the flexibility to interpret federal regulations to broaden eligibility and streamline students’ application and recertification process. For example, states can make students at public colleges eligible for SNAP who are in career and technical programs of study or in programs that enhance their post-graduation employability. States like Massachusetts, Oregon, New York, and California have taken advantage of these provisions, and other states should follow their lead. Similar opportunities exist within Temporary Assistance to Needy Families (TANF), federal child care subsidies, and programs in other areas.

Minoritized students are disproportionately represented in community and technical colleges. Yet in virtually all states, community colleges receive far less funding and their students receive lower levels of financial aid.Despite more affordable tuition and fees, students at community colleges often face higher out-of-pocket costs than students at four-year institutions. States should significantly ramp up operating support for community colleges and ensure their students receive the same, or greater, financial aid.

Minoritized students are more likely to face basic needs insecurity and less likely to be able to draw on family wealth to meet emergency needs or unexpected expenses. Institutionally-funded and operated emergency aid grant programs have already demonstrated impressive results at several colleges and universities, and federal funding under the Higher Education Emergency Relief Fund provided essential support for students.[67] Two states, Washington and Minnesota, offer state-funded emergency aid programs, which offer a model for emergency aid beyond the federal and institutional level.

States should ensure that part-time, adult-learner, and transfer students have equitable access to state financial aid and repeal financial aid criteria based on academic performance, such as standardized test scores, grades, or satisfactory academic progress. Furthermore, state financial aid should also reach students enrolled in private HBCUs, TCUs, and MSIs. State financial aid awards should be “first-dollar” whenever possible so that students receiving Pell Grants do not miss out on critical financial aid. Finally, state grant awards beyond tuition and fees should be usable for non-tuition expenses, such as textbooks, food, and housing. The proposed HBCU Opportunity Fund and related investments in Virginia can serve as inspiration.[68]

Hunger-Free Campus legislation creates a bundle of interventions to tackle student hunger, including expanding funding to address food insecurity and connecting students with programs like SNAP.[69] This legislation can channel significant resources to colleges to pilot or expand innovative and locally tailored anti-hunger efforts, and supporting efforts to educate students about public benefits programs for which they may be eligible.

Recommendations for College Administrators, Faculty, and Staff

In June 2023, the U.S. Supreme Court effectively ended race-conscious admissions policies at colleges and universities (also known as “affirmative action” in admissions). The Court’s radical ruling was a setback for efforts to make higher education more inclusive and equitable, and to address racial disparities in enrollment. However, nothing in the Court’s ruling prevents institutions of higher education from using alternative methods to improve the diversity of their student body and to better serve those who are admitted—including by meeting their basic needs. As a landmark report by the U.S. Department of Education makes clear, “there remain legally permissible ways to advance the critical mission of socioeconomic and racial diversity in American colleges and universities.[70] It is essential for institutions of higher education to remain steadfast in their commitment to examining, addressing, and closing racial disparities in student success and wellbeing. Colleges should help to meet the basic needs of minoritized students as a central pillar of these efforts.

This report details significant disparities in basic needs security among minoritized students. Due to the legacy of systemic racism, wealth inequality, and substantial differences in economic security, minoritized students often struggle to afford college costs, even students who have little to no unmet need on paper, or those from families who might not be formally considered low-income. Institutions should work hard to keep tuition low and affordable, provide need-based financial aid, and minimize unmet need. At the same time, colleges must ensure that their “cost of attendance” accurately reflects student expenses, or they may run out of the financial aid they need to meet their basic needs. [71]

Many students remain unaware of public benefits and campus supports or have misleading perceptions of eligibility requirements. Colleges can remedy this by making this information accessible through multiple channels, including personalized emails and text nudges, and ensuring that students who are likely to be eligible for public or tax benefits receive proactive guidance on how to apply.

Many students remain unaware of existing emergency aid sources.[72] Colleges and universities can take the most direct steps to remedy that problem by advertising existing aid programs more broadly, ensuring aid application processes are free of stress and stigma and getting funds to students fast. Given declines in enrollment during the pandemic, colleges should also consider distributing emergency aid to former students to encourage re-enrollment and degree completion. And, colleges should consider establishing institutional funding for emergency aid now that federal pandemic funds are gone.

Discuss basic needs during enrollment, orientation, registration, and in the classroom. Parenting students and those caring for family members require flexibility to attend classes. Faculty should accommodate students’ needs and share information about campus supports and public benefits on course syllabi.[73] Make basic needs professional development mandatory for the college community so faculty, staff, administrators, and institutional leaders share a mutual understanding about its relevance as a retention strategy, are equipped to promote access, and encourage students to seek support.

Colleges should engage work-study students and student leaders to become basic needs ambassadors and promote awareness and utilization of services available on-campus and in the community. It is important to involve those who have utilized campus support services (e.g., students who have experienced basic needs insecurity) to help give feedback on marketing, communication, and application materials and resources to ensure that they are accessible and student-friendly.

Colleges and universities can make seeking out help as stress-free as possible for students by ensuring they can access all resources—public benefits, on-campus supports, etc.—in one place.[74] This will require collaboration between front-line staff, college leadership, and faculty. Establishing external partnerships with community-based organizations, community health centers, and government agencies to provide social services and non-academic assistance has shown promising results at other colleges[75] and will ultimately strengthen students’ ecosystem of supports.

Many people and organizations contributed to this report. Data collection for the 2020 #RealCollege Survey was possible thanks to financial support from the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, Gates Philanthropy Partners, and the Prentice & Alline Brown Foundation. We are also grateful for our partners at all participating colleges and universities and for the more than 195,000 student participants. Students’ experiences are foundational to understanding the realities of navigating higher education, and we are endlessly grateful to the students who shared their experiences with us.

The Community College Equity Assessment Lab (CCEAL) would like to acknowledge the students who participated in the focus groups with our team.

Many current and former Hope Center staff contributed to this report’s completion:

- Research and writing: E. Christine Baker-Smith, Amy Ellen Duke-Benfield, Sara Goldrick-Rab, Tom Hilliard, Mark Huelsman, Bryce McKibben, Anne E. Lundquist, Michael Reid Jr., Paula Umaña, Sara Abelson, Christine Leow, Stacy Priniski.

- Communications: Rjaa Ahmed, Lauren Bohn, Joshua Rudolph.

The findings and conclusions contained within are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect positions or policies of our funders.

[1] The Hope Center at Temple University. (2021, March). #RealCollege 2021: Basic needs insecurity during the ongoing pandemic.

[2] Baker-Smith, C., Coca, V., Goldrick-Rab, S., Looker, E., Richardson, B., & Williams, T. (2020, February). #RealCollege 2020: Five years of evidence on campus basic needs insecurity. The Hope Center at Temple University.; National Student Clearinghouse Research Center. (2021, November). COVID-19 Stay Informed Series: Fall 2021 Enrollment.

[3] Jones, T., Nichols, A. H. (2020). Hard truths: Why only race-conscious policies can fix racism in higher education. The Education Trust.

[4] Clinedinst, M. & Patel, P. (2018). 2018 state of college admission. National Association for College Admission Counseling.; Garcia, S. (2018). Gaps in college spending shortchange students of color. Center for American Progress.

[5] Saenz, V.B., Garcia-Louis, C., Drake, A. P., & Guida, T. (2017). Leveraging their family capital: How Latino males successfully navigate the community college. Community College Review, 46(1), 40-61.; Wood, J. L., & Harris III, F. (2018). Experiences with “acute” food insecurity among college students. Educational Researcher, 47(2), 142-145; Wood, J. L., Palmer, R. T., & Harris III, F. (2015). Men of color in community colleges: A synthesis of empirical findings. Higher Education: Handbook of Theory and Research, 30, 431-468.

[6] Bhutta, N., Chang, A., Dettling, L., & Hsu, J. (2020, September). Disparities in wealth by race and ethnicity in the 2019 survey of consumer finances. Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System; Price, A. (2020, February). Don't fixate on the racial wealth gap: Focus on undoing its root causes. The Roosevelt Institute.

[7] Garcia, S. (2018).

[8] Smith, D.A. (2021, September). Achieving financial equity and justice for HBCUs. The Century Foundation.

[9] Baylor, E. (2016). Closed doors: Black and Latino students are excluded from top public universities. Center for American Progress.

[10] Anthony Jr., M. (2021, April). Building a college-educated America requires closing racial gaps in attainment. Center for American Progress; Libassi, C. J. (2018). The neglected college race gap: Racial disparities among college completers. Center for American Progress.

[11] National Student Clearinghouse Research Center. (2021a). Fall 2014 entering cohort six-year outcomes by race and ethnicity and gender.

[12] Anthony Jr., M. (2021, April).

[13] National Student Clearinghouse Research Center. (2021, October 18). COVID-19 Stay Informed Series: Fall 2021 Enrollment.

[14] National Student Clearinghouse Research Center. (2021); The Hope Center at Temple University. (2021).

[15] The Hope Center at Temple University. (2021).

[16] Kienzl, G., Hu, P., Caccavella, A., Goldrick-Rab, S. (2022, February). Parenting while In college: Racial Disparities In basic needs Insecurity during the pandemic. The Hope Center at Temple University. .

[17] Dahl, S., Strayhorn, T., Reid, M. Jr, Coca, V., & Goldrick-Rab, S. (2022, January). Basic needs insecurity at Historically Black Colleges and Universities: A #RealCollegeHBCU report. The Hope Center at Temple University & Center for the Study of HBCUs.

[18] Federal Bureau of Investigation. (2020). Active shooter incidents in the United States in 2020.

[19] GBD 2019 Police Violence US Subnational Collaborators. (2021, October). Fatal police violence by race and state in the USA, 1980-2019: a network meta-regression. The Lancet, 398(10307), 1239-1255.; Kishi, R., & Jones, S. (2020, September). Demonstrations & political violence in America: New data for summer 2020. Armed Conflict Location & Event Data Project; Taylor, D. B. (2021, November 5). George Floyd protests: A timeline. New York Times.

[20] Note: The term "Asian American" refers to those with ancestry from East, Southeast, and South Asian backgrounds.

[21] Center for the Study of Hate & Extremism. (2021). FACT SHEET: Anti‐Asian prejudice March 2021.

[22] Rogin, A, & Nawaz, A. (2020, June). ‘We have been through this before.’ Why anti-Asian hate crimes are rising amid coronavirus. PBS.

[23] Redden, Elizabeth (2021, April). Students seek tangible changes in face of anti-Asian hate. Inside Higher Ed.

[24] Green, E. L. (2020, March). Colleges get billions in coronavirus relief, but say deal falls short of needs. New York Times.

[25] Brown, R. (2017). Higher education and inequality. Perspectives: Policy and Practice in Higher Education, 22(2), 37-43.

[26] Note: 19 focus groups were conducted in person, and four were conducted virtually via Zoom

[27] The Hope Center’s definition of students’ basic needs was modified from one used by the University of California. For their definition, see: Regents of the University of California Special Committee on Basic Needs. (2020, November). The University of California’s next phase of improving student basic needs.

[28] U.S. Department of Agriculture, Economic Research Service. (2020). Food security in the U.S.: Measurement.

[29] U.S. Department of Agriculture, Economic Research Service. (2012). U.S. adult food security survey module: Three-stage design, with screeners.

[30] See web appendices for details on The Hope Center’s measures of housing insecurity.

[31] The survey questions used to measure homelessness were developed by researchers at California State University. For information on the items, see: Crutchfield, R. M. & Maguire, J. (2017). Researching basic needs in higher education: Qualitative and quantitative instruments to explore a holistic understanding of food and housing insecurity. For the text of the McKinney-Vento Act, see: The McKinney-Vento Homeless Assistance Act of 1987. Pub. L. No. 100–77, 101 Stat. 482 (1987). See web appendices for more details about the measure of homelessness.

[32] Meltzer, A., Quintero D., & Valant, J. (2019). Better serving the needs of America’s homeless students. The Brookings Institution.

[33] Willis, R. (2018). How members of parliament understand and respond to climate change. The Sociological Review, 66(3), 475-491.

[34] Federal Communications Commission (2016). 2016 broadband progress report; Herder, L. (2021, Aug 1). Broadband access still a struggle for tribal colleges and universities, 18 months into the pandemic. Diverse Issues in Higher Education; Harrison, D. (2021). Affordability & availability: Expanding broadband in the black rural south. Joint Center for Political and Economic Studies; Hayes, J, Gao, N., & Hiseh, V . (2021, November). Policy brief: achieving digital equity for California’s students. Public Policy Institute of California.

[35] Goldrick-Rab, S., Coca, V., Kienzl, G., Welton, C. R., Dahl, S., Magnelia, S. (2021). #RealCollege during the pandemic: New evidence on basic needs insecurity and student well-being. The Hope Center at Temple University.

[36] Hoyt, L. T., Cohen, A. K., Dull, B., Castro, E. M., Yazdani, N. (2021). “Constant stress has become the new normal”: Stress and anxiety inequalities among U.S. college students in the time of COVID-19. Journal of Adolescent Health, 68(2), 270-276

[37] Hoyt, L. T., Cohen, A. K., Dull, B., Castro, E. M., Yazdani, N. (2021). “Constant stress has become the new normal”: Stress and anxiety inequalities among U.S. college students in the time of COVID-19. Journal of Adolescent Health, 68(2), 270-276; Huckins, J. F., DaSilva, A. W., Wang, W., Hedlund, E., Rogers, C., Nepal, S. K., Wu, J., Obuchi, M., Murphy, E. I., Meyer, M. L., Wagner, D. D., Holtzheimer, P. E., Campbell, A. T. (2020, June). Mental health and behavior of college students during the early phases of the COVID-19 pandemic: Longitudinal smartphone and ecological momentary assessment study. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 22(6); Copeland, W. E., McGinnis, E., Bai, Y., Adams, Z., Nardone, H., Devadanam, V., Rettew, J., Hudziak, J. J. (2021). Impact of COVID-19 pandemic on college student mental health and wellness. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 60(1), 134-141.e2.

[38]Abrams, Z. (2021, July 1). The mental health impact of anti-Asian racism. American Psychological Association 52(5), 22.; Kishi, R., & Jones, S. (2020, September). Demonstrations & political violence in America: New data for summer 2020. Armed Conflict Location & Event Data Project.

[39] Stone, M.D., Mack, K.A., & Qualters, J. (2021, February). Notes from the field: Recent changes in suicide rates, by race and ethnicity and age group — United States, 2021. Weekly I, 72(6), 160-162. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

[40] Adams, L.B., Baxter, S.L.K., Lightfoot, A.F., Gottfredson, N., Golin, C., Jackson, L.C., Tabron, J., Corbie-Smith, G., & Powell, W. (2021, June). Refining Black men’s depression measurement using participatory approacheds: A Concept mapping study. BMC Public Health.

[41] Watkins, D.C. (2012). Depression over the adult life course for African American men: Toward a framework for research and practice. American Journal of Men’s Health, 6(3), 194-210.

[42] Lederman, D. (2020, April). How teaching changed in the (forced) shift to remote learning. Inside Higher Ed.

[43] Strayhorn, T. L. (2021) Investigating the impact of COVID-19 on basic needs security among vulnerable college students: An exploratory study. Academia Letters.

[44] Goldrick-Rab, S., Hacker, N. L., Kienzl, G., Price, D. V., & Curtis, D. (2021b). When care isn’t enough: Scaling emergency aid during the pandemic. The Hope Center at Temple University.

[45] Any public assistance includes SNAP, WIC, TANF, SSI, SSDI, Medicaid or public health Insurance, health services, childcare assistance, unemployment compensation, transportation assistance, tax refunds, veterans' benefits, services from nonprofit agencies, legal services, LIHEAP, utility assistance, and housing assistance

[46] Vise, D. and Lonas, L. (2023, April). Community college enrollment plunges nearly 40 percent in a decade. The Hill.

[47] Fishman, R. and Cheche, O. (2023, February). Why didn’t the community college students come back? New America Foundation.

[48] McKibben, Bryce. (2023, August). Making College Financial Aid Flexible and Responsive: The Case for Continuing the Federal Investment in Emergency Grants. The Hope Center at Temple University.